Company Details

Englewood, Colorado (a wholly-owned subsidiary of U.K.-based Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd.)

Founded: 1981 (company); 2008 (U.S. subsidiary)

Privately owned

Employees: 20 in Colorado (about 600 in U.K.)

Surrey Satellite is helping its customers get small payloads off the ground and into space.

Surrey has been the top small satellite manufacturer in the U.K. for more than 25 years, but the company only established a U.S. operation relatively recently. Company officials picked Englewood as its HQ across the pond because of the deep talent pool.

"Colorado has the second largest space industry behind California," says CFO Becky Yoder. "We're responsible for the United States and our parent company handles the rest of the world."

Every single one of the company's more than 40 missions to date has been on time and on budget. "It's a phenomenal legacy," touts Yoder. "We're building off of that success here [in Colorado]."

While the small satellites have been the subject of much buzz lately, the reality is different, she adds. "Everybody says they're getting into small satellites, but none of them have the heritage we have."

The company manufactures many components in the U.K., but the company is scaling up its operations in Englewood. "We're building up our capabilities," says Yoder. "Surrey is very vertically integrated -- 92 to 93 percent of our spacecraft, we make. We basically make everything other than batteries and parts of the solar systems."

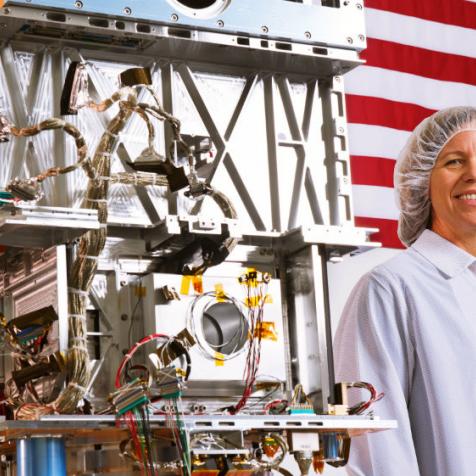

Technicians in Englewood are currently working on the company's first Colorado-made satellite, OTB-1 (short for Orbital Test Bed), which will carry the Deep Space Clock from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) into orbit from Cape Canaveral in Florida in 2016.

"It's our spacecraft and you buy a ticket to ride," says Yoder. The OTB "is going to be a product line for us. There's a lot of payloads that are orphaned. We'll get them to space economically."

The payloads have applications ranging from navigation to imagery to measuring the wind speed of a cyclone. "The whole idea behind the Orbital Test Bed is to help companies exploit space," explains Yoder, noting that it's common for companies to get federal funding to build a payload but not have the funding to launch them.

"We're talking $10 million to $15 million, which is far less than they're used to spending," Yoder says.

The launch of OTB-2 will follow soon after OTB-1, possibly in 2016 as well. "We take 18 to 24 months to go from a spacecraft order to launch," Yoder notes.

Surrey's strategy dovetails into NASA's proclaimed pivot to outsourcing, but Yoder says that's been more talk than reality to date. "NASA's talked about it a lot, but they haven't been able to do it," she says. "It's hard for the government to wrap its head around it."

But OTB-1's cargo from JPL might just provide the necessary nudge for real change. "It's a new buzzword," says Yoder. "Everybody is saying 'hosted payloads,' but it's business as usual for us."

Challenges: Being early to market. "It's still a little bit leading-edge," says Yoder of the Surrey model. The big hurdle is "getting the government to recognize a different risk posture and different funding."

Opportunities: "I think the opportunities are endless, because there are so many orphaned payloads," says Yoder. And the model should spur a wide range entrepreneurs who previously thought they were priced out of the satellite market.

Needs: "Export control," says Yoder. "Everybody complains about it in the space industry. It makes it so difficult."

GPS is just one example. "You're talking about commercial satellites," she adds. "It's not rocket science sometimes. It really does limit how we globalize space."

![]()